Leadership Most Flawed

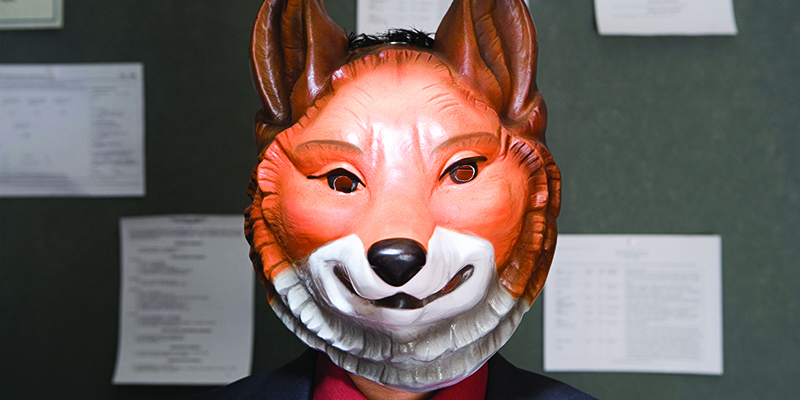

The rise and disastrous fall of five American CEOs.

By Timothy Inklebarger | Winter 2016/17

America’s love affair with its entrepreneurs and executive titans is uncanny—think Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Jobs and Shark Tank. But as much as we love building them up, so too do we enjoy tearing them down.

Take, for instance, the recent case of scandal-rocked Wells Fargo & Co. and the sudden departure of its shamed chief executive John Stumpf.

Stumpf resigned amid the discovery that employees of the once trusted bank, under pressure from bank executives to meet challenging sales quotas, opened two-million bogus customer accounts. Stumpf likely will walk away with $130M in total compensation, but Wells Fargo made an unexpected move to clawback $41M in stock options from the exiting bank boss.

Meanwhile, Stumpf has been vilified by lawmakers like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who accused him of “gutless leadership.” What’s more, customers and bank employees—they’ve filed a $2.6B class-action lawsuit against the bank—have taken to social media to call out his mismanagement.

Experts say putting CEOs like Stumpf on a pedestal is as old as business itself; who can forget early industrialists and inventors like Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller and Thomas Edison? But nowadays the stakes are much higher for executives, in large part due to the oversized paychecks they receive compared to their counterparts.

Whether a CEO destroys a company due to mismanagement or fraud, or a combination of both, stockholders increasingly are less willing to give them a second chance, experts say.

Rick Wartzman, senior advisor at the

Drucker Institute at Claremont Graduate University, says more mainstream business news has more people paying attention, which means greater scrutiny when signs of poor management begin to surface. But despite that, CEO pay has tended to move in only one direction—upward. And even when CEOs are ousted, they typically receive rich exit packages.

“I would argue the biggest thing that’s changed over the last few decades is the way we compensate our CEOs,” he explains. Wartzman, author of the forthcoming book T

he End of Loyalty: The Rise and Fall of Good Jobs in America and a contributor to Fortune magazine, points out that executive compensation averaged about $1M through the 1970s, and doubled to $2M in the 1980s. The trend has continued through today, where executives are earning annual compensation packages in the tens of millions of dollars.

In May 2016,

The New York Times identified Dara Khosrowshahi, CEO of Expedia, as the highest paid executive of 2016, earning $94.6M, most of which was in stock and options, according to CNN Money. The median pay for CEOs in 2015 was $16.6M,

The New York Times reports.

To put it all in perspective, the pay of executives like William Seawell, failed CEO of Pan Am airline in the early 1980s, compared to the frontline Pan Am worker was probably a ratio of about 30 to one, says Michael Connor, editor of

Business Ethics magazine. “Now we’re in the range of almost 300 to one. The numbers are so huge that people just don’t have any tolerance for error. Those numbers imply that you should be perfect or near perfect; so when an executive screws up in a major way people won’t stand for it anymore.”

Connor says this dynamic has propped up CEOs as “mythological figures” who are saviors tasked with making a company successful.

Wartzman echoes that notion, saying the justification for ridiculously high CEO pay is that they’re worth it because of the value they’re creating for shareholders.

“I think it feeds into the mentality of ‘Wow, look at what the CEO did.’ But what person does that alone?” Wartzman asks. “There’s an entire management team behind them and tens of thousands of workers behind them on the frontlines. Why put all the good things that happen in the hands of this one person?”

Being a larger-than-life persona can be a double-edged sword. When business leaders succeed, we hail them as geniuses, but when that prosperity flounders, out come the torches and pitchforks.

To illustrate, here are five CEOs who rose to be household names before learning the hard way that when the going gets tough, it’s often the person on top who’s forced to get going.

Ken Lay, Enron

Deregulation of the natural gas and electric power industries in the 1980s and 1990s allowed Ken Lay to grow Houston Natural Gas Co. into what would eventually become the $68B energy giant Enron Corp.

Enron would later become one of the most notorious examples of corporate corruption and fraud. Twenty-thousand Enron employees lost not only their jobs, but also their life savings—much of which was in company stock—when widespread accounting irregularities were discovered and the company collapsed.

Lay, chairman of Enron, and Chief Executive Jeffrey Skilling, among others, were “cooking the books” and overstating profits and stockholder equity. Meanwhile, the executives were giving themselves hefty bonuses and compensation packages, and selling hundreds of millions in Enron stock as the company was imploding.

Lay was found guilty of six counts of conspiracy to commit securities and wire fraud and died of a heart attack before his sentencing. Skilling was convicted of conspiracy and fraud and insider trading, and is currently serving a 14-year prison sentence.

“Deregulation only works when you have a mechanism to prevent fraud,” says James Hawley, a professor of management at St. Mary’s College of California, explaining that corruption in the boardroom, like the kind seen at Enron, happens when executives don’t have “skin in the game” founded on good business practices, such as compensation through restrictive stock that vests over several years.

Chuck Conaway, Kmart

In 2000, Chuck Conaway was tasked with turning around the ailing retailer Kmart, which was facing tough competition from the big-box behemoth Wal-Mart. Many believed that Conaway’s prior success as president and COO of CVS made him the right CEO to rebrand the store and rehab its failing supply chain. They couldn’t have been more wrong. Now, Conaway is often viewed as one of the worst offenders—as his ship was teetering, he also hid slumping sales from regulators and stockholders.

Conaway started out on the right foot, bringing back the Blue Light Special and closing losing stores, among other reforms. But within two years, the turnaround agent was sent packing. It was later revealed that he tried to cover up a liquidity crisis in the months leading to Kmart’s 2002 bankruptcy.

The SEC charged Conaway and his CFO with financial fraud in 2005, claiming, “Conaway and [Kmart CFO John] McDonald lied about why vendors were not being paid on time and misrepresented the impact that Kmart's liquidity problems had on the company's relationship with its vendors, many of whom stopped shipping product to Kmart during the fall of 2001.”

Conaway, along with other Kmart executives, also spent millions in loans from Kmart on boats, airplanes, home renovations, and other luxury items, and ultimately was ordered to pay the SEC a $5.5M settlement.

Andrea Jung, Avon

Scandal often leads to a CEO’s downfall. Other times mismanagement brings about an ultimate demise. With former Avon executive Andrea Jung, it was both.

In 1999 Jung was promoted as the makeup and beauty products company’s first woman CEO. Jung pushed to expand Avon into international markets and stumbled repeatedly with failed restructuring ventures over the next decade. The breakdown of Avon’s supply chain and news of a bribery scandal in China caused Avon’s stock to plummet in 2011.

Bloomberg named her one of the top five worst CEOs the following year, noting “the company’s value has fallen under her watch from $21B to $6B.” What’s more, Avon was forced to pay $300M in legal expenses over the foreign bribery case.

Business Ethics magazine’s Connor says the myth of the CEO as a savior “can lead to a calamitous situation” because it enshrines them as the embodiment of all that is good and bad in the company. Before running Avon into the ground, Jung was celebrated, serving on the board of directors of both General Electric and Apple. She was seen as having the Midas touch, until Avon stock began to nosedive.

“Business leaders are important and play an important role in a company,” Connor says. “But too many people buy into the myth that one person can make a company successful.”

Mark Pincus, Zynga

Avon’s Jung was joined on

Bloomberg’s 2012 worst CEOs list by Mark Pincus, the man who served twice as the computer game company Zynga’s CEO—and was twice ousted from the position.

Though fraud and conspiracy are at the heart of some of the most spectacular CEO fails of all time, the absence of wrongdoing won’t necessarily protect leaders from history’s harshest critics. Pincus is a case in point.

In 2012 Bloomberg stated that Pincus miscalculated by “hitching his company’s wagon too securely to Facebook, which Zynga relies on for a big chunk of revenue.” (The company created popular online games such as FarmVille and Words With Friends.) He also got dinged in the press for selling millions of shares in Zynga stock, a move that “hardly expressed confidence in the company’s prospects,” according to Bloomberg.

Nevertheless, Zynga brought Pincus back as CEO in 2015, but gave him the boot less than a year later.

William Seawell, Pan Am

Navigating the vagaries of the ever-changing tech industry would be a challenge for any business leader, but failure to maintain dominance in an industry defined by a rapidly growing marketplace is a story as old as business itself. William Seawell learned this quickly upon becoming CEO of Pan Am in 1980.

Seawell found himself in a tough spot due to the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, which dismantled Pan Am’s monopoly over international flights.

“Pan Am thrived in a heavily regulated environment,” says Connor. “When the industry became more competitive Pan Am wasn’t prepared for it.”

Deregulation, combined with the miscalculations of purchasing National Airlines and expanding its fleet of 747s pushed Pan Am’s debt to $1B and ultimately brought the company down.

The so-called “Queen of the Skies” was forced to sell the Pan Am Building—now known as the MetLife Building—in Midtown Manhattan for $400M, and Seawell was pushed into early retirement.

Whether because of poor judgment, poor management or outright criminal intent, when the mighty fall they fall hard. And they usually take whole companies down with them.